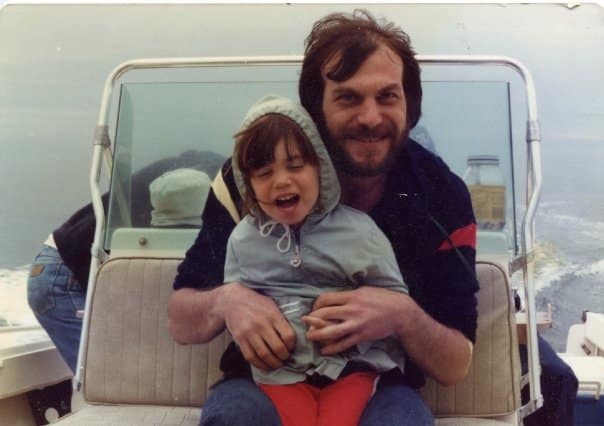

I inherited a blue sink-side sponge and the chore of washing up at the age of 15, when my mother left my father to live in an apartment on the other side of town.

It wasn’t an especially laborious job—we had a dishwasher. But some pans needed extra help. Caked-on macaroni and cheese. Chicken and dumplings. High-calorie Southern comfort foods prepared by a woman my father hired. The kind of food my mother never allowed. We were all watching her weight, and mine.

Besides being ineffectual for scrubbing, the blue sponge squicked me out. Bits of food clung to it, penetrating its pores. I tried to get it clean, but fragments remained. There it sat, by the side of the sink, mocking my incompetence.

This wasn’t my only incompetence. I sensed early on my mother always had one foot out the door, stunned by the reality of marriage and two toddlers at the age of 20. An overindulged child-woman ill-prepared to care for anyone but herself, and barely even that.

I did everything I could to make her stay. I made no demands. I super-sensed her needs and moods. Allowed her the spotlight—her need to be special. But she left anyway, and an uneasy silence prevailed as my father, brother and I rebuilt lives to fill her absence.

Really, when I looked forward to my future, my kitchen incompetence wasn’t that big a deal. I never planned to be a typical suburban homemaker. If I imagined any future at all, it was that of the caricature of the reclusive spinster living with seven dogs.

I never wanted children. The level of certainty was 99.9%. I couldn’t bear the idea of continuing the cycle of damage to a child the way I was damaged—not maliciously, but through ignorance and the self-centeredness that comes from a parent’s stunted emotional development.

One day I was in Baby Gap buying a shower gift. I was 38. I glided from display table to hanging rack, enchanted by the tiny garments. One-piece things I later learned were called onesies. Little pants with ingenious snaps down the inside of the legs. Tiny matching skullcaps with tufted knots on top, all in the softest cotton knits. I selected the most adorable outfit, presented it at the checkout, and began to cry.

I wouldn’t say I set a conscious intention to find a husband and make a child, but I believe I unconsciously shifted in that direction. I had devoted years of therapy with the goal of becoming more functional, more whole. Maybe some part of me was beginning to think it was possible.

I met my future husband, Michael, walking our dogs at St. Mary’s-by-the-Sea along Black Rock Harbor in Bridgeport, Connecticut. I had seen him before, walking with a woman and pushing a two-year-old in a stroller. I found out later they were his sister-in-law and nephew.

After we dated for a while, I confessed my lack of desire to have children, but he didn’t seem to care—or maybe he thought I’d change my mind.

When I was 39, Michael and I returned home from a whirlwind trip to Arkansas—for Thanksgiving dinner and an introduction to my family—and then a three-hour drive south to visit an old childhood friend and her husband.

My friend and I discussed my childbearing ambivalence.

“He’s wonderful!” she gushed, basing her statement on his interactions with her own children. “He’ll help you.”

She spoke from the view of the already-initiated parent, who knows that rearing children often means you just step up and put one foot in front of the other. That there’s no magic involved—only duty…and love. My desire finally overpowered my fears. I decided to believe her.

On our flight back to Connecticut, Michael and I discussed getting busy ASAP because at our age, we realized it might take a while. We conceived the night we got back.

Around Christmas, after taking three pregnancy tests, all positive, I called my father with the happy news.

“Call me back when you’re married.” He slammed down the phone.

Stung by my father’s reaction, I felt compelled to contact my mother even though we had long been estranged and spoke only infrequently. When she heard the news, I was surprised to see that her excitement paralleled my own. This was the encouragement I needed to resume contact. We started phoning regularly. She was the first witness to my first trimester morning sickness when she called one evening and Michael reported that I was throwing up dinner and couldn’t take the call.

When Ian was a newborn, she came to visit during the torrential rains from Tropical Storm Floyd. She cooked and washed dishes and did laundry and let me nap while I recuperated from my c-section and tried to pump milk out of breasts scarred from breast reduction surgery. I knew in advance I would likely have trouble, because of the surgery, but I wanted to try anyway.

When Ian was nearly two, he and I took a road trip to visit her in Virginia Beach. One night I knelt in front of the bathtub, laughing with Ian as I watched him splash with his toys. I turned, feeling her presence in the doorway, watching us.

“You’re a good mother,” she said.

I immediately understood this was her way of saying she knew she hadn’t been. Of apologizing. Making amends. I grabbed onto it. I knew it was a gift not many get.

A year later, I was again in her Virginia Beach apartment, this time without Ian. I had come to say goodbye, a job that needed all my attention. I was in the small kitchen with my sister-in-law, Sam. Sam had nursed her sister through cancer and her eventual death. She knew what to do.

Another blue sponge sat by the sink.

“Lord, look at this raggedy old thing”. She picked it up and laughed at its bedraggled appearance.

I said, “It’s probably the same one we had when she lived at home with us.”

We dissolved into a giddy laughter that skirted the edge of hysteria, fueled by our lack of sleep from 3 a.m. alarms, set to rouse us to administer pain medication.

I felt a twinge of guilt, laughing at the expense of my mother, who was dying in the next room.

I had never seen anyone dying of cancer. Witnessed its brutality. But what surprised me was seeing her courage in coping with it all. On the way to chemo, stopping the car so she could get out and vomit by the side of the road. And then promptly after chemo, nausea somehow abated, indulged her yen for chocolate milkshakes, which she never permitted herself before she became sick. The once vain woman I’d known refused a wig for her bare head, but instead haunted the hat aisle in Target. She tried on silly hats, inspected her reflection in the mirror, and laughed.

After she died, I went through her possessions. The ones not in the will. The everyday objects that reveal the essence of a person.

In a brown crocodile handbag, I found a series of green butterfly-shaped cards with notes on each. I realized she must have used these cards to tell her story—her Al-Anon story.

Long-timers in 12-Step groups share their stories aloud in agonizing detail. It is a way of admitting and accepting responsibility for one’s own shortcomings and failures, describing one’s road to recovery, and sharing a sense of hope as an act of service to others in all stages of recovery.

Some of her notes were cryptic—”clues Craziness of alcoholism checkbook” –but some I could extrapolate the meaning. She had left my father for another man, Mike, who became her second husband. An alcoholic grifter who initially gave her the attention she craved and never got from my father, a workaholic driven to build financial security designed to protect him and his family from the privations he experienced as a child in the Depression.

Another butterfly card read “unable to keep a job”. Once Mike blew through her inheritance, he left her. She had reached her proverbial “bottom” and found redemption through Al-Anon. Just as I used psychotherapy to make myself whole, she used the 12-Step framework. No matter how it’s done, I know it takes courage. And I admired her for that.

I had always told others that my mother and I were nothing alike, but in truth, we were more so than I ever realized.

Except in our regard for the blue sponge.

Benay Yaffe grew up in Arkansas and got her B.A. in psychology from the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma, and her M.A. in Marriage and Family Therapy from Fairfield University in Connecticut. Benay was a freelance reporter and photographer for Newtown Patch in 2010 but she believes the other jobs she’s had over the years (children’s tennis instructor, metal sorter, psychiatric technician and HMO customer service rep) were equally valuable in her path to becoming a writer. She lives in Newtown, Connecticut, with her husband, two dogs and two cats. She is a new empty nester, and her son appreciates that she limits herself to one phone call and two texts a week.

*****

Wondering what to read next?

We are huge fans of messy stories. Uncomfortable stories. Stories of imperfection.

Life isn’t easy and in this gem of a book, Amy Ferris takes us on a tender and fierce journey with this collection of stories that gives us real answers to tough questions. This is a fantastic follow-up to Ferris’ Marrying George Clooney: Confessions of a Midlife Crisis and we are all in!

***