By Allison L. Palmer

I threw up in the bushes outside the hospital the day my sister was born. I didn’t stomp my feet and demand that my mom shove her back up there or refuse to go hold her. I didn’t hop up and down and beg my dad to bring me inside so I could kiss my brand-new best friend. No tantrums, no joy. Just vomit. I stopped right next to the E.R. entrance, put my hands on my dimpled kindergartener knees, and barfed. My dad looked down at me with a crease between his eyebrows as I wiped my mouth on the sleeve of my sweater. He knelt next to me and patted my back, checking my forehead for fever. Yes, I feel better now. He shrugged and took my hand as we walked through the doors. Even then, my body knew the things my head didn’t. This is gateway love. My sister was my first. She will probably be my last. Maybe we have to empty out parts ourselves to make room for everything new.

My dad made space for us. Now that I’m older, I see that he was always up ahead of me. Carving away splinters, repainting colors, clearing cobwebs. He could blow clouds from the sky as easily as I could make a birthday wish. My childhood had soft edges. When I was ten and my sister was five, he took us on a trip to a small island off the coast of Canada. He drove us around in a red rental car with the windows down. July air rolled in off the St. Lawrence River, warm and light blue. He pulled the car off the road at the point of a finger. Anything we wanted. Waterfalls, homemade jam, sheep in a field. For me, we stopped at four used bookstores in a day. He popped sour cherries in my sisters’ mouth whenever she started to pipe up and spun her around in circles so I could empty the stacks into baskets with no limit. I wasn’t picky, not even a little bit. While I glossed over titles and artwork, I willed the piles to grow until they reached the ceiling and enclose me, unreachable, in a fortress that smelled of ink, where every wall and window would be made of paper and I would never run out words.

Growing up, I read the same books over and over until their covers fell off. I stole from libraries. I learned from The Lovely Bones that it’s easy to keep things that aren’t yours and make them yours, in more ways than one. I stuck V.C. Andrew’s Flowers In the Attic under my sweatshirt because at the time, it looked huge and menacing and exactly like something I shouldn’t be reading. I didn’t let that thing go until all 400 pages of arsenic and incest and locked doors and mothers who shouldn’t be mothers were branded on my brain. As Cathy and Chris descended their knotted sheet rope to the lawn of Foxworth Hall, I chewed gum and thought about evil. Then ordered the rest of the series on the internet along with the audiobook of Lolita because the jacket art, a girl in sunglasses sucking on a lollipop, seemed undeniably and captivatingly wrong. For days, I laid crumpled on my bed and cried to Jeremy Irons unidentifiable accent. I cried for Humbert Humbert and for the way people can’t fix their hearts, cried because I thought Dolores was undeserving. Cried because nymphets probably do exist. I filed away that word away under “L” for lust, love, lies and loneliness. All of the above. I took to organizing everything I read in books into neat boxes in my head.

After I’d finished gutting the bookstores and the sour cherries had dwindled to just pits and stems, we took a drive up the coast of Bas-Saint-Laurent to see the whales. We wrapped ourselves up in neon orange wind jackets with matching pants and climbed into an aluminum airboat, barely scraping 25 feet long. My dad sat in the middle and tucked my sister under one arm and me under the other. The guide alternated excitedly between English and French in the same breath. My dad kept his eyes on the horizon as the land behind us became nothing more than a thin green strip. I was watching the sun glint off his glasses when the guide began exclaiming things in Frenglish and making big gestures and everyone on the boat stood up. I gripped back of my seat and craned my head around their legs. My dad sat unmoving, but he had pushed his glasses up on his head. He took my face in his palms and turned it out to sea. The blue whale is the biggest living thing on the planet. 200 tons. Its body looked more silver than blue and it stretched an incomprehensible distance, rising in and out of the waves. I held my hands up to the sides of my eyes like blinders and worked my way down the length, head to tail, trying and failing to put boundaries on its existence. Its mouth was the size of the boat. If it opened its jaws, we might drift inside and float for an eternity along an endless shoreline of bones and blubber. I leaned closer into my dad’s side. There might be someone in there right now. We probably couldn’t hear the shouting.

I saw a dead whale about a year later. I could put limits on this one, easily. The three of us had just moved to a beach cottage in the wrong season, the middle of the winter. The ocean was our backyard and we talked there on weekends, down eleven flights of stairs worn splinterless by the saltwater and wind. Even in the frost, the rot smell was still strong enough to make my eyes water. I breathed exclusively through my mouth. Only a hulking skeleton was left, taller than me, with grey flesh still clinging on in some places. My sister was hardly a quarter of its pelvis, toddling around the perimeter like a lost duckling who has mistaken its mother for a corpse. I had never been that close to something so dead. I felt something next to sadness. In the backyard of reverence, but not quite. No one makes coffins that big. I stood in its ribcage and next its open eye sockets. Bizarrely inside and outside all at once. While we explored, we must have talked about how it ended up there, beached, alone, and now three quarters decayed. The likely death. I tried to chase away the gulls that hovered around the body, but more came. Before we left, I took off my gloves and bent at the edge of the waves to rinse my hands. The water was so cold it burned. I thought of the man sailing along the gut of the blue whale, calling out to empty, unforgiving waters and I felt small.

On the way back from the coast, we stopped at an antique-ish gallery surrounded by gardens. My dad admired its history. I’d been promised a stop at the bakery next door. The building was a refurbished barn made of smooth wood painted yellow with big windows. Windchimes tinkled and swayed around all the doors, betraying the way it had settled quietly into the background. I wondered if ghosts could make noise. Inside, the walls were cluttered with paintings of distorted faces and oversized clocks and sculptures made of things like obsidian and repurposed wire netting. I wandered absent-minded up and down the aisles, brushing my fingers along the eclectic treasures. My favorite bauble was a carving of a ballet dancer with movable parts. Her joints were set on loose hinges and splayed out in all directions around a fringe of white tool. I held her by her tiny wooden waist and rolled her head around between my fingers. The little dancer’s face was blank, expressionless. I imagined a soft smile should have been painted there, along with sleepy half-closed eyes. Something fuzzy, out of focus, and full of grace. I imagined she had a lot of secrets.

The thing about a body made of wood and set on hinges is that begins to stiffen. Arms that once stretched seamlessly through space now barely extend. Legs that once leapt and faltered without abandon start to creak. The thing about being afraid of your own body is that it becomes a stranger. I think this is what we think grace is, partly. Ethereal fear floating under your heart. We mistake it a lot of the time for beauty. As I learned to dance, my body lengthened and hollowed out right before my eyes. My teacher’s name was Ms. Mary. She sat always in the front, always in black, doling out critiques like sunshine and lightning. I remember we were practicing pirouettes for the fourth time that week. We practiced and practiced, with red cheeks and quick breaths until all of us turned together but we couldn’t stop because one girl in the back kept falling. Her name was Maggie. I could see her out of the corner of my eye, pulling herself off the floor, madly blinking back tears. Ms. Mary shook her head in slow motion, then called out my name. She instructed me to stand in front of Maggie, so she couldn’t see herself. She was getting in her own way. Stand there and don’t move. The other girls silently parted as I crossed the studio and aligned myself carefully in the mirror. The top of Maggie’s auburn bun was just visible above my head. She was taller than me. Keep going, Ms. Mary said. Until she gets it right. As she turned, I could sense every hot cheek in the room blistering until the heat fried away every nerve that said to scream, to run, to throw yourself on the floor along with her until we were all unmovable, peaceless, quiet. Lovely in our paralysis. I heard Maggie hiccup as she stumbled and hit the floor again and I retreated completely inside myself. I felt the grains of wood overtaking and splintering along my skin and straightening my spine, felt my face rounding out to nothing. Get up. My ribs began shrinking down onto my lungs and grasping hold of my throat. Her breath came faster and began breaking into sobs and the thing about being afraid of your own body is that you can’t leave. There isn’t anywhere else to go.

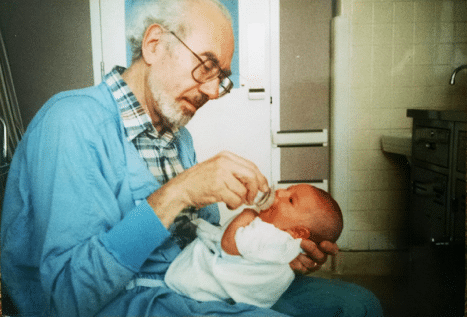

There was a sharp smack on the window over my head. The figurine fell out of my hands and clattered onto the floor. I hadn’t even noticed that the sky had opened up and was now heaving down rain. I ran towards the noise and found my dad and sister kneeling just outside the door. I peeked around their shoulders and saw a bird half-limp in my dad’s hand, maybe six inches long, with black and white tipped wings. It was laying on its side, little legs outstretched and stiff. Poor thing got confused in this weather and flew straight into the window. Wispy noises came out its beak. It reminded me of my sister when she was a baby and how she cooed while she slept. I used to sneak into her room to run the tip of my pinky along her jaw until she would bat my hand away in her sleep. I dropped to the floor in front of her crib before she could wake up. Must be in shock. My dad shook his head and set the bird down gingerly under the edge of a bush. He took my sisters hand and reached for mine. Come on, let’s go. I was still looking down. Its black eyes were lolling around wildly in its skull and its body had started twitching. The muscles had nothing to hold on to, like a little girl who can’t stop falling long enough to stand.

In second grade, a boy I knew died. He stabbed me with pencils and tripped me on the basketball court at recess and I hated him. He gave me a scar, on my right knee. Shaped like a T. Then an ATV flipped over on top of him in the woods and he was brain-dead before my scab hadn’t even fallen off. My mom brought me to the funeral, and we sat in the last pew of the church waiting for a eulogy that no one managed to deliver. She handed me green and blue Sweetarts from her purse and I sucked on them until my tongue was numb. The casket was open, filled with stuffed animals and sports trophies and an entire embalmed life. I looked at my feet and fidgeted and tried to pray even though I had absolutely no idea how to. I am still uneasy in long lines and in silence. My knee itched and I could see the fresh pink skin peeking out from underneath the scab. I wondered what happened to cuts and scabs when you were dead. When I picked mine off eventually, it didn’t bleed. The skin was permanently puckered. I dug my nail into it, to no avail. A tiny spot of nothing. I remember I laid on the hillside outside the church with my mom after it was over and held her while she cried. Both of her parents died when she was 16. She likes to say that I saved her life. I wonder if now she loves less because I’m branded by a dead kid. The thought is fleeting. On the outside, my body is only 99% alive.

Before I could stop myself, I had reached out and taken the bird in my own two hands, cupping it against my t-shirt like a newborn. I laid down on the grass, tucking my knees up to my chin. The wet blades glued themselves to my limbs and cradled my head and left trails of goosebumps like comets on my exposed skin. I didn’t hear the hectic symphony of the windchimes clanging to a fever pitch. I think a small coffin must be much easier to build than a big one. If I could, I’d build one myself, from the softening wood of my body. This is close enough. Didn’t feel the icy rain drops that slid down my spine and under the rain coat my dad must have laid over me. For once, the cold was freeing, limitless. I could swim through it for an eternity. Didn’t notice when the storm had gone, and the sun lit the backs of my eyelids pink. My thoughts were replaced with all the words I’d ever read in books. It’s like when you drop something heavy on a floor covered in dust and the world goes away, just for a second, in the disarray. When it clears, I see my small sister’s face pressed into the grass in front of me. Her eyes are open, and calm. In them, are the parts of myself I thought had gone. When she places her hands over mine, I think about how hearts sound like they are gulping. Like they want to break out of your chest and drink in the air, how they crave leftover life, the 1%, and how there is nothing else like the impossibly tiny body underneath both sets of our fingers.

Allison Palmer is an undergraduate student and new writer. She studies Biology and English at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Her other work can be read online in Pithead Chapel and Eunoia Review. We are THRILLED to be featuring her work.

Upcoming events with Jen

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE ALEKSANDER SCHOLARSHIP FUND