By Maggie Bucholt

Loretta watched her mother loading packages of toilet paper into a huge cardboard box, then folding yards of wrapping paper patterned with hot-pink roses around the monster parcel. Her mother’s lips twisted in a hateful way as she taped the seams and tied the box with a purple ribbon so dark it was almost black.

“Mom, it’s…” Loretta folded her arms across her chest, wondering if Frances had forgotten her pills—or swallowed too many. She frowned, searching for the right word. She was about to say mean, but thought better of it. “Why not give Gran a nice pocketbook?” She nibbled a cuticle on her thumb. A drop of blood appeared, and she licked it away.

Frances—as Loretta had started referring to her mother in her head—signed her name to the card. Gran’s birthday was Saturday, three days away. Frances tucked the card under the ribbon when she was finished. Skinny arms stuck out of her short-sleeved blouse, and there were deep circles under her eyes. Watching TV news images of wounded soldiers in the jungles of Vietnam kept up her up at night.

Loretta was desperate to leave for college in August, ten months away, ready to start her own life; she had put in her time taking care of Frances. But all she could think about was how her mother would fare when she left. She would have to convince Gran that Frances could live on her own and not have to return to that horrible place. The nurses with their plastic smiles and their squeaky orthopedic shoes, the padded rooms behind the corridor’s locked doors. The first time when Frances had gone away for a “rest,” she had come back subdued. After she returned this time, she had been acting weird, as if they had fried all the normal parts of her brain along with the sick ones.

Ignoring her, Frances stood back and examined her work. “The lady in the Hallmark store said the gift was a hoot. Maybe I should get a job on Newbury Street wrapping fancy presents.” Frances removed the bobby pin from her stringy hair and repinned it. Then she laughed, without joy. Ha, ha, ha. “It’d probably pay more than my job at the card shop.”

“You’re working?”

A job. Proof that her mother was doing well, despite the ridiculous gift. Loretta seesawed between hope and doubt that this job would last any longer than the others Frances had had in the past three years since the last hospital stay. She ticked the jobs off in her head: Saleswoman at Jordan Marsh in Boston, and cashier at the five-and-dime, waitress at the diner on the main street of their suburban town. Frances argued with everyone—supervisors and co-workers, her own mother, and Loretta. She found fault with the downstairs apartment in Gran’s two-family house and brought up every injustice, present and past: the broken change machine at the Laundromat to Gran’s refusal to let her prune the rosebushes to her husband dying young.

“Why not?” Frances said.

“I’m glad, Mom, really.”

“You should be. The sooner we start saving, the sooner we can leave, just you and me, the way we planned.”

“Don’t you get tired of saying the same thing every year?” The walls in the living room were as bare as the day they moved in ten years ago, after her father’s car accident. Don’t bother to hang anything up, Frances had said. We won’t be here long.

Her mother whipped out a large manila envelope from the drawer under the white Formica counter. She waved it near Loretta’s face. “What’s this, huh?”

Loretta snatched the envelope and glanced at the return address. The brochure from the university in Colorado. Would be a good fit, her art teacher had said. “That’s my mail. You know what it is.”

“Still dreaming, are you? Well, stop, because you’re not going. We’re leaving here together.”

“Gran is paying the tuition, paying for everything.”

“Did she tell you what to study too?”

“You never say anything nice about Gran.”

“Because there is nothing nice to say.”

“What about her letting us live here without paying rent, taking care of me when you were… away.”

“You’ll see.”

They glared at each other. Frances was the first to look away, and a moment later the tension lines around her mouth deepened. “Oh, go on. Get to your room. You spend enough time studying in there anyway. Brush your hair, will you? And stop biting those nails.”

“At least I wash my hair.” Loretta ran her hand over her thick, long hair that never lay flat. “At least, I… ” Worry about what will happen to you.

Loretta closed the bedroom door, grateful to be alone. The last of the sunlight filtered in between the blinds, casting dark bars onto the beige rug. A car horn beeped twice, a sharp sound that echoed down the street. She peeked through the blinds. Old Mr. Tierney pulling his Buick out of his driveway. The beeps were his farewell before driving to the VFW to drink away the pain of losing his son in Vietnam. Oh, she hated this crummy neighborhood, and especially Mr. Tierney’s mousy wife who asked in a pitying tone, “How is your poor mother?” as if she were ready to hear the truth. That gossip would murmur something falsely reassuring before turning away, like everyone Loretta had tried to confide in.

Father Donovan, she avoided too; he pretended not to understand her predicament, and whenever he stopped her to talk about faith or about the children’s art program where she had taught the previous two summers, his breath smelled as though he hadn’t brushed his teeth for a week. No, the faith she had was in herself, and the only thing she liked about mass was watching the votives that burned as insistently as her desire to leave home.

She set the college materials on the blue-gingham quilt and went to the bureau. Under the bottom drawer, she felt for the fat envelope taped there, savings from her two summers of working and from birthday gifts from Gran. Eight hundred and fifty dollars and twenty cents. The bills were crisp, new, like the life she envisioned far away from Frances. She replaced the money and slid the college materials under the mattress with the others before fixing the sheet, hospital cornered, the way Gran had taught her.

In the living room, Frances had her legs tucked up under her on the sofa, transfixed in front of the TV. Her cigarette case rested on the lace doily that hid the threadbare arm. A plume of smoke from her cigarette wafted up toward the ceiling.

“Where you going?”

“Upstairs.”

**

Loretta entered her grandmother’s apartment without knocking. The living room smelled of lemon polish, and the crowded apartment had everything Loretta and her mother’s didn’t: gold-framed bucolic scenes on the walls, heavy red-brocade drapes on the windows with sheer curtains underneath, a china cabinet with Waterford crystal, and a grandfather clock with handsome Roman numerals, Loretta’s favorite.

“Gran?”

“In the bedroom, sweetheart,” her grandmother called.

Her grandmother sat at a dressing table with a three-paneled mirror, smoothing cold cream over her plump cheeks and under her eyes, lifting, then straightening her silver-frame eyeglasses. The bottom of Gran’s tent-like, navy-blue dress, the kind that hid her fat stomach and thighs, grazed the carpeting.

“You hungry?” Gran said. “I was about to start dinner.”

“Mom’s making spaghetti,” Loretta said, not meeting her eyes. She hated to lie, but it was easier to let Gran think that her mother was able to boil water.

Loretta ran her fingertips over the polished dressing table with its little atomizers of fragrances, the cobalt-blue Evening in Paris bottle, and the tubes of lipsticks on a glass tray. The thought of seeing Paris, especially the Impressionist paintings, Degas, Monet, Cezanne, that she had read about in books, made her smile. It was a dream she hadn’t shared with Gran yet.

She perched on the edge of the bed and leaned back, resting on her hands. The deep green comforter was silky beneath her palms. Watching the rhythmic strokes of her grandmother’s hands putting on lotion was a soothing ritual that had started in her childhood. Gran would pick up Loretta’s small hand, press it to her lotioned cheek, then to her lips for a noisy kiss. It made Loretta laugh when she wanted to cry. Everything will be fine, Gran seemed to say. It was Gran who sewed the ripped shoulder of her Raggedy Ann doll, and washed and ironed the small dress and white apron. Gran who had helped her with homework. And it was Gran who had given her the little booklet after Loretta noticed pink spots on her underpants when was she was twelve.

Gran told her a story she had heard a gazillion times, and Loretta wondered if her grandmother would begin forgetting more and more things, the way old people did. It was the story of how Gran survived the death of her young husband so many years ago. Unlike Frances, Gran was quick to remind her, she had found a job in a factory, at a time when not many women worked. Eventually, Gran had met and married a widower, the grandfather Loretta knew, before being widowed again.

“I had to do what was best for me.” Gran gazed at Loretta over the tops of her glasses. “You, too, have to figure things out, think of yourself.”

“Yes, Gran.” Loretta started to chew on a fingernail, before her grandmother gave her a warning look. She dropped her hand.

“Because no one else will.” Gran turned this way and that in the mirror, examining her wrinkled face before wiping the excess cream from her misshapen arthritic fingers. “How are things at school?”

“A’s in English, history, and biology.” Loretta plopped back onto the bed, pleased that her grandmother listened carefully as she talked. But an A- in math. She vowed to study harder, when she wasn’t taking care of Frances—she didn’t do sports or afterschool clubs. “I asked each teacher what was expected for me to get an A, and then I made a list and completed the extra assignments.”

She never mentioned she ate alone in the cafeteria or the bitchy girls who never invited her to their tables. She imagined the way they saw her: a too-tall girl who kept to herself and painted posters for school plays. Instead she talked about the library book with the glossy photos of the works of Monet.

Gran nodded approvingly. “You’re serious, not like your mother, marrying your father before she graduated. She could have finished college, if she let me help her. Stubborn, too stubborn she was. You know, your mother was always… different. I suppose losing your father was too much. Goodness, the shock was too much for me.”

“Mom is making an effort,” she said, feeling hopeful. It wasn’t as though she didn’t love Frances; her mother was the only parent she had left, not counting Gran. “Mom’s ….” She stopped. She would tell Gran about the job at the card store only if it lasted more than a week.

Loretta jumped up and from behind, wrapped her long arms around her grandmother’s bosomy frame, conscious of her height—tall like her father, Gran always said. She put her cheek to her grandmother’s and rocked her back and forth, eyeing both their reflections in the mirror. Gran, her short gray hair done up at the beauty parlor every week; and she, Loretta, with hair ballooning around her thin face, was about to start the rest of her life.

“Oh, you’re being so cool, Gran, about college and all.”

“I want you to begin your life the right way. Plenty of good colleges close by, in Boston.”

“Around here?” Her voice faltered. They had never talked about where she would attend college, and she was taken aback. “A university out west is what I was thinking. I’ve never been there, of course.” She was excited by the prospect of studying in a place she had never been, of traveling to Paris after college graduation. “I don’t know about Boston.”

“Think about it.” Gran patted her arm.

Later, Loretta sat on the back porch steps with the sketchbook and charcoal pencil for the preliminary drawing of the cardinal. A lone leaf zigzagged toward the ground. The bird in the denuded maple tree cocked its head, as though it were waiting for her to begin. A sketch for her senior art portfolio. Focus. She inhaled deeply. Focus. Empty your mind, the art teacher said, when she struggled with a sketch in the art room. Let your hand work its magic over the paper.

But she was unable to draw, her thoughts ricocheting from dissuading Frances on Gran’s present to convincing Gran about Colorado to improving the application essay so she would be accepted. Tomorrow she would show Gran the brochure and talk up the Art History major. Long after the cardinal flew away, she stayed where she was, staring into the autumn twilight.

**

The following afternoon, Loretta was home from school late, and when she heard Gran’s voice in the living room, her insides somersaulted. Gran’s birthday was two days away. Why was she here? She jabbed her jacket onto the brass hook. Gran hadn’t been inside the apartment in months.

Frances was on the sofa, legs crossed, the couch springs squeaking in rhythm with her wobbling foot. She had on a flower-print dress that Loretta hadn’t seen her wear in a long time. The red lipstick, smeared outside the natural contour of her lips, looked as though it been applied by a three-year-old. Frances’ tremulous smile was so wide, Loretta thought her face might crack.

Gran, her posture straight as a knife, sat on a kitchen chair; the sofa was too low for Gran. Gran shot Loretta an accusing look. Why didn’t you tell me?

“Loretta sweetheart, isn’t it nice your mother is working again?”

Frances turned to Loretta and raised an eyebrow. The eyebrow almost reached the uneven part in her hair.

“Yes, it is.” Loretta glanced nervously at the mammoth box with the dark-purple ribbon on the TV console. She still had to figure out what to do and quickly. She tugged down the hem of her sweater and perched next to Frances on the sagging seat, smoothing her plaid skirt over her knees.

“You feel up to doing this, this job?” Gran grasped the strap of the big black purse in her lap. She snapped the clasp open and closed, open and closed. Click, click. Click, click.

“She’s doing fine, aren’t you, Mom?” But Loretta could see her mother didn’t appear fine at all and, worse, Gran could too. Frances’s gaze darted around the room, and she pressed a folded piece of paper into her lap.

“I wouldn’t have taken the job otherwise, Mother,” Frances said, a slow flush spreading up her neck to her face.

“Now Frances, I didn’t mean anything by it.” Gran winked at Loretta. In her own way, Gran was trying.

“Don’t start, Mother,” Frances said. “That’s not why I invited you in.”

“No, then why did you?” Gran gazed at Frances over her glasses that had fallen to the middle of her nose.

Frances’s foot bobbed faster. And Loretta tensed. She leaned over and whispered, “Don’t give Gran the present. Please.” Her mother struggled away from her.

“To say that we will be moving out as soon as I save some money,” Frances said.

Loretta groaned inwardly. She had heard the argument many, many, many times before. But at least she hadn’t given her the birthday present. Don’t say anymore, Mom. Don’t.

Gran seemed to consider this without rancor and adjusted the purse on her lap. “I see. And what apartment do you think you can afford, on a card-store salary?”

“Here’s the budget,” Frances said, her tone triumphant. She unfolded the paper and dropped into Gran’s lap. “An apartment’s for rent a few blocks from here.”

“Mom.” A flare of hope sparked in her chest.

Gran adjusted her glasses and made a show of studying the numbers. “This isn’t going to work.” Her words sliced the air.

Frances’s lipsticked mouth worked, but no sound came out. She sank onto the sofa and crossed her legs, staring into space. Loretta could tell by her grandmother’s stricken gaze that she knew she had gone too far and didn’t know the way back.

“Gran, come on, it’s a start,” Loretta said quietly. “You could help with a plan.”

Frances shot up, and before Loretta could whisper in her ear that this wasn’t the right time, Frances snatched the huge birthday present from the console and placed it at Gran’s feet. Frances’s smile was as gleeful as a mischievous child.

“For your birthday, Mother,” Frances said. “A couple of days early.”

“Why, thank you, Frances,” Gran said. A look of astonishment, then happiness flickered across her plump cheeks.

Loretta slid her moist palms down her skirt as Gran tore off the dark ribbon and wrapping paper. Gran sorted through the packages of toilet paper as if she were searching for something. Was there a real present hidden among the paper that she was missing?

“A little joke. Right, Mom?” Loretta, her face hot, tried to laugh.

“I don’t see the humor.” Gran’s thin lips pursed.

“You get what you deserve, you mean old thing!” Frances started laughing, the same mirthless sound as when she had wrapped the toilet paper.

“Mom, stop.” Loretta tried to put her arms around her thin shoulders, but Frances pushed back in an irritated way, a smirk on her face.

Gran stood up to leave, trembling.

“Gran, wait.” Loretta was desperate to do something, anything to lessen the animosity. She ran to her bedroom for the bright yellow box with the black fancy script, the Jean Nate gift set she had bought, and at the last moment stuffed the university brochure into her skirt pocket.

“Happy birthday, Gran.” Loretta handed her the present. “I, I didn’t get a chance to wrap it.”

“Thank you, sweetheart.” Gran swayed a little, holding her purse and the yellow-and-black box. “You’re a good girl, a very smart girl.”

Gran had fixed her gaze on Frances, and Loretta stiffened. “Gran, let’s go.”

“Which is why Loretta will do well at college,” Gran said.

“Mind your own business, Mother.”

“Won’t you do well, Loretta?” Gran said, turning to her, with fiery eyes.

Loretta wished she were outside sketching the cardinal. Or unpacking her things in the dorm at the university in Colorado. Or painting the long view of the Eiffel Tower from the banks of the Seine.

“Come on, I’ll walk you up,” she said, and steered Gran toward the door.

Upstairs, she stood near the grandfather clock and trimmed a fingernail with her teeth. For once, Gran didn’t scold her about biting her nails. Gran moved slowly to hang her coat in the closet. Neither of them spoke. Gran seemed to collapse into the dining room chair.

“Mom’s doing OK, she does have that job.” Loretta hoped she sounded convincing.

Gran sighed and opened her arms, and Loretta moved in for an awkward embrace. She could smell Gran’s lavender-scented lotion.

“Did you think about what I said? About Boston?” Gran ran her hand over the polished surface to the table, brushing away imaginary crumbs.

Loretta pulled out the colorful brochure. “Colorado, see for yourself. The college has an Art History major and I…”

Gran shook her head. “Come now, sweetheart, did you think I wouldn’t be the one to decide? I will be paying for everything.”

“I didn’t realize that meant I couldn’t go where I want.”

“Look at you, getting all upset. I’m your champion, sweetheart. All I’m saying is that the college has to be closer to home.”

Loretta shifted from one foot to another, feeling miserable. “Because that’s best for you, Gran,” she spat. “That’s not fair.”

“Not for me, either.” Gran gave her a wan smile. “I can’t take care of her forever. I’m not getting any younger.”

Back downstairs, Loretta emptied a can of tomato soup into a pot and added water, trying to swallow the panic that stuck in her throat. The blue flame flickered under the pot. She had fooled herself into thinking she would be free, first at college, then after graduation. Free to do what she pleased, live wherever she liked. The realization that she could not left her cold. She stirred the soup with a wooden spoon. The soup sloshed over the sides. Mom had to eat something, had to feel better. She hoped the aroma would lure Frances into the kitchen. At the table, she opened her loose-leaf and turned to the unfinished college essay for Colorado, the one giving her the most trouble, perhaps because it was her first choice. Empty your mind, focus. But she couldn’t shake off the dread. Of course Gran expected her to take care of Frances when Gran no longer could. There was no one else.

“So what do you talk about with your grandmother when you’re up there?” Frances stood in the doorway, one hand on her hip. Loretta was surprised that Frances seemed fine, as though all she needed was a few moments rest to clear her head and change her vengeful mood.

“School, stuff.” She shoved the essay into her loose-leaf. She had gotten good at hiding the truth. The soup gurgled and the tomato-y scent filled the kitchen, and she stirred the pot. She had expected shouting, angry words from her mother, not this. An argument she could deal with. A self-pitying mother, she couldn’t.

Her mother lit a cigarette and shook the match until the flame died. She inhaled deeply, and smoke shot out of the side of her mouth. “You’re going to leave, aren’t you?”

Loretta didn’t answer. She got out two white bowls from the cupboard, ladled steaming soup into one, and set it on the table. Frances slipped into a chair and balanced her cigarette on the lip of the glass ashtray. She dipped the spoon into the soup. Halfway to her lips, she dropped the spoon back into the bowl, splashing soup all over the table.

“Mom, you’ll do fine.” Loretta wiped up the soup with a wet sponge. Another lie. Shame washed over her. “You can save money like you said and move, if that’s what you want to do,” she said, wishing she could believe her own words. “You don’t need me.”

Frances sucked on her cigarette, eyeing Loretta. “That store needs a better manager. I told the woman she could ask me whatever she wanted, that I’d help her run the place. She got all huffy.”

Loretta filled a bowl for herself and tasted the soup. The soup had a bitter, metallic taste, as if she had boiled nickels along with the tomatoes. She listened to her mother complain about the smart-alecky salesmen and the lumpy grilled cheese sandwich she had for lunch at the diner where she used to waitress. At last Frances stubbed out her cigarette, and all Loretta could feel was relief that the terrible moment, when she feared hearing the words I do need you, had passed.

**

At lunchtime the next day, Loretta shifted in a hard-seated chair at the guidance counselor’s office, one of two chairs that faced Mr. Crowley’s desk. The desk was cluttered with pens, pencils, forms, and a half-eaten, smelly tuna sandwich. Piles of college catalogues were lined up with precision on the floor.

“I’m having trouble with this essay for Colorado, my top choice.” Loretta pushed the two-page draft for the university in Colorado across his desk. “Could you take a look at it?”

“Certainly, give me a moment,” he said. He was a short man with a round face and a snub nose. The kids called him Porky behind his back. He jotted notes in the margins. After a few moments, he reviewed the essay, point by point, and suggestions to add why sketching and painting were so important to her.

“I have no doubt you’ll be admitted to a good college with your grades.” As he talked, he rubbed at a stain on his green-striped tie. “Have a backup plan, besides Colorado. Did you want me to review the other essays and applications?”

“I’ve already finished three.” Loretta tucked the essay into her loose-leaf. “They’re at home.”

“Good girl. I know they’re lengthy.”

“You, ah, said something about financial aid, when I came in before. My grandmother offered to pay but I’m not sure about.…”

“It can’t hurt to apply for financial aid, no matter what your resources. Colleges offer grants based on aptitude as well as need.”

He handed her a thick packet, and she listened carefully as he explained the different federal grants and work study. She thanked him and stuffed the daunting paperwork into her loose-leaf, hoping she wouldn’t have to fill out those applications too; she still hoped to persuade Gran about Colorado.

“I tried telephoning your mother, so she could be here.” Mr. Crowley nodded at the empty chair.

“She’s working, Loretta said quickly. “She won’t have time.”

“I can help you start filling out the aid forms, if you like. Just come in again.”

Back home after school, Loretta opened the front door and heard the soft, unmistakable sound of weeping coming from Frances’s bedroom. She dropped her bag and struggled out of her jacket. Disappointment knifed her insides. Frances had been fired. Why else would her mother be home before five o’clock? She ran down the hall and pressed her ear to Frances’s door. She knocked lightly.

“Mom?” She tried the doorknob. Locked. She waited, resting her forehead against the doorframe. “It doesn’t matter,” she said through the crack, willing herself to sound upbeat. “You know I love you, right?”

The wailing turned to loud sniffles.

“You can find something else. Mom?”

In the kitchen, she sipped a glass of milk and nibbled an Oreo. She would have to help Frances get past this setback, find the right job. Only she didn’t know how. The scribbling on the pad by the telephone caught her eye. An enormous X crossed out Mr. Crowley. A panicky feeling swept over her, and she hurried to Frances’s door. She stood outside, biting a nail, contemplating what she could say, something to soften the truth. But nothing came to her. She sighed. Frances would have to hold her own when she was gone.

Loretta opened the door to her own room, bent on making Mr. Crowley’s suggestions to her essay, and flipped on the light switch. She stood stock-still. Her sketches were torn from the wall, her dresser drawers emptied and left half open, her sweaters and underwear strewn on the floor, along with the blue-checked quilt. Balled up in the corner were her bed sheets, and her mattress hung off the box spring at an odd angle.

A pile of cut-up paper and the kitchen scissors were on top of the naked mattress. She picked up a sliver of paper with her name still visible. The essays and carefully filled-out applications had been shredded into millions of pieces. Her heart banged against her ribcage. She rushed to the bureau and pulled out the bottom drawer. The thick envelope with the money was still taped to the bottom. She shoved the envelope into her waistband of her skirt. She ran down the hall and pounded on Frances’ door with her fist—bam, bam, bam—until the side of her hand ached.

“How could you?” she shouted. Her pulse drummed in her ears. “I’ve always helped you, been on your side.”

No answer. She rattled the knob in frustration, picturing how Frances, her face blotchy red with rage, had overturned everything, cut all the paper with the same expression of gleeful revenge she had worn when presenting Gran with the monster package of toilet paper.

She flew up the stairs to Gran’s, her chest heaving, but at the top, she stopped and stared at the closed door. A college closer to home, Gran had said. I will be paying for everything. She gripped the banister, sick at heart and frightened. When had she ever been able to change Gran’s mind about anything? Gran would expect her to stay after graduation, too, find a job, and do what she had always done to keep Frances out of that dreadful place. Loretta turned and started downstairs as though she were sleepwalking.

In the apartment, she picked up the sketchpad and charcoal pencil and went out to the back porch. The sun was low in the sky and she gulped the cold, fresh air. She sank onto the wooden steps. From the Tierneys next door, she heard the grating sound of a metal rake and the rustle of brittle leaves. She glanced over. Mrs. Tierney was focused on clearing a path to the street. The lifeless leaves had been raked into organized piles.

The envelope in her waistband pressed into her side, and she placed a protective hand over the money for a moment, her mind churning with everything she had to do—she would ask Mr. Crowley for help with the paperwork—and the lies that she would have to tell until she left. She would learn to forgive herself for leaving Frances, the way she had learned everything else that Gran had taught her.

She opened the sketchpad and smoothed a new sheet of paper. The solitary cardinal appeared, bright red against the maple’s dark bough, and seemed to watch her. She assessed the cardinal, making tentative strokes at first. The strokes became bolder, deeper as the image of the cardinal took shape on the page. The body, the sharp beak, the unblinking black eyes. Then she drew the bird’s legs, fragile but strong.

Maggie Bucholt a graduate of the MFA in Writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and was awarded a fellowship at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts to work on her novel. A story, “Deer’s Leap,” was a finalist in the Arts & Letters: Journal of Contemporary Culture fiction contest. Her credits include an essay, “Rhyming Action in Alice Munro Short Stories,” in The Writer’s Chronicle, and “Death and the Desire to Live Deliberately,” in Desire: Women Write About Wanting, published by Seal Press.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

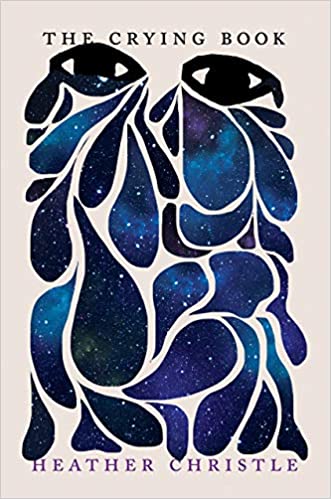

A book about tears? Sign us up! Some have called this the Bluets of crying and we tend to agree. This book is unexpected and as much a cultural survey of tears as a lyrical meditation on why we cry.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~