By Zoë Brigley Thompson

I start to like my father again when we are standing together looking at a painting. To begin, you would have to explain the place. The Musée D’Orsay in Paris was a railway station until 1939, and the great clock-faces on the exterior signal an obsession with timekeeping and travel. This particular painting is relatively small, and its intimacy is out of place under the arching glass roof where trains once ran. The museum is a public space and still has the feeling of a railway station with people hurrying to their next destination. In the middle of all this is a painting of a woman’s genitals, and my father and I are standing together in front of it.

I have just turned 18, and my father has brought me to Paris as a birthday present. Some years before, my father moved with his new wife to the central lowlands of Scotland, but he often rings on the phone. “Just hop on a plane and come over for a visit,” he says, but of course it is never that simple.

What my father does not know in Paris is that I am in a very precarious place. A few years before, I swore that I would never have sex again: my first experiences were that awful. Not long after that, I slept with my best friend just for the sake of it, to get it over with.

I look at my father curiously. My experience of men is not huge. I can’t trust that he will always be kind. Though he often laughs and jokes, something is wrong with my father. When I ask my grandmother about him, she recalls one of his teachers stopping her outside the school gates and asking, “What’s wrong with your son?” She replied, “I was hoping that you could tell me.”

He describes himself as the “man who never was.” He is talking about the myriad jobs in which he never found satisfaction. He is talking about the journeys and trips he made – South America, Asia, Europe – never finding fulfillment. He is talking about the many women he took up with and later rejected.

I never heard my father tell anyone that he loved them, but he might have said so, in private, to one of the women he dated, or perhaps to my mother. Because he must have felt something. Much later, over dinner in Philadelphia, when I am a “grown-up,” my father will tell me that he never wanted to be a father, but a friend. I will say, “I have enough friends.”

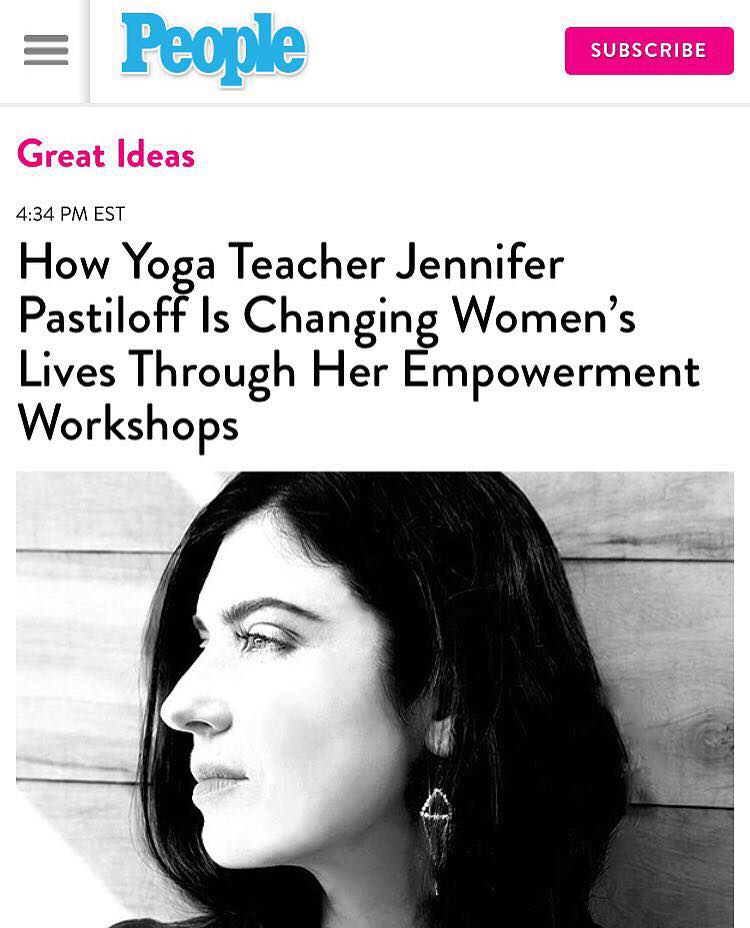

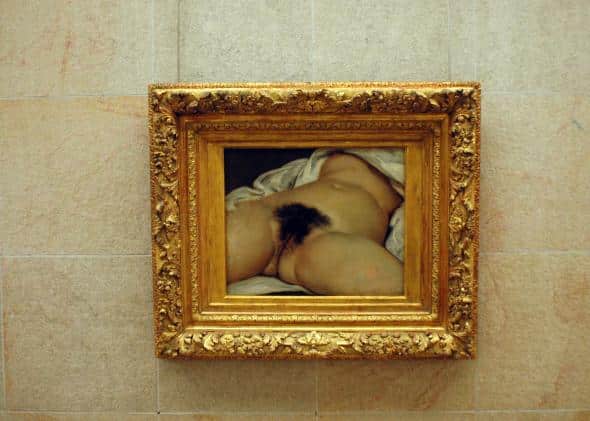

Still, the Paris galleries are enchanting, and I love looking at paintings with him. There is always some detail that he notices – a glint of light, a hint of a color, a clue. We spend a long afternoon in the Musée D’Orsay, but one painting in particular strikes me: Courbet’s The Origin of the World.

At 18, I have not seen many pictures up-close of female genitalia. Once entering a sex shop for a dare, I glimpsed the vagina of pornography: the lurid gash of sex magazines. The painting is different: a gorgeous female torso, the breasts and head mainly covered by a sheet, a round stomach, the pubic hair and genitals, and thighs lounging open. I notice how visitors skirt around the picture as if nervous to be caught standing in front of it.

I stand by the painting with my father. He is never the type to be easily embarrassed by sexuality, and now he looks admiringly at the painting with genuine interest. He doesn’t recoil from it in horror, or find it embarrassing, or think it is offensive. I find something to like in him then: that he is never prudish about sex, but likes and enjoys women.

My father and I don’t know each other very well, but in that moment in front of a painting in Paris, he helps me in some small way, because he celebrates the female body and refuses shame. What is still to come is finding my own pleasure, and, eventually, I do.